Homage to a Hyphen

Table Talk chats with Jawahar as he shares his memories of growing up in a hyphenated India and confesses his love for all things akuri.

It’s safe to say that children born in the late ’80s in urban India, inherited the notion of ‘India’ through drab textbook accounts of battles won and lost, emotionally charged Bollywood movies and perhaps glamourous accounts of parties with “gore sahibs” in novels. For me, it’s only in the last decade or so, did history seem to expand itself; facts and stories flowed into each other creating a world that begged to be explored. While unpacking centuries worth of existence may seem like the work of a lifetime, I do find myself drawn to that hyphened existence of a nation. A hyphen, whose shadow shows up in the most surprising nooks and crannies of daily existence. And a plate of food is no exception.

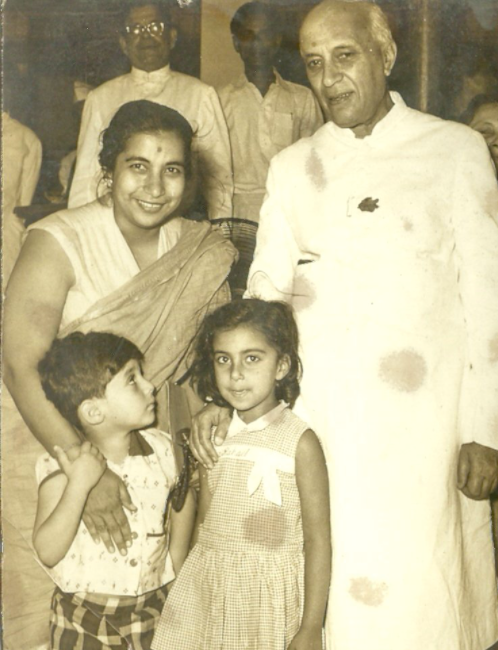

I was thrilled to spend an evening chatting with Jawahar Ezekiel, lovingly called Joe Uncle in the family, to explore this more. Through the crackle of a patchy Zoom call, we began the journey by him in Durgapur in the ’60s. Durgapur then, a town in West Bengal, was a township that had only recently come into its avatar of an industrial hub, finding its feet in a young, independent India. It is in this backdrop and in the arms of an enigmatic mother who loved to cook and host parties for her husband’s Steel Plant colleagues, did Joe Uncle’s love for food flourish.

The Steel Plant community of Durgapur, set up in the late ’50s, was in many ways influenced by a certain “western way of eating”. It comes as no surprise then, that our conversation begins with the all popular “continental cuisine”. A cuisine brought to the Indian shores by erudite Englishmen, as they tried their hands at fashionable French cooking, or in other words ‘food from the continent’. This cuisine transformed the humble vatana (green pea) into an “English vegetable”, slathered in a creamy cheese sauce. It brought in souffles and baked dinners and even gave the elite, exclusive clubs the cutlet.

Interestingly, this cuisine seeped into home kitchens. Joe Uncle talks about his mother laboriously cooking roast ducks dinners, caramel custards and chicken tetrazzinis in her imported oven. “She was such a popular party host! One time, she created a mashed potato sculpture in the shape of a chicken and 4x5 ft sized cake! Imagine that in sultry Durgapur!”, shares Joe Uncle. He takes me into the deep alleys of this memory lane as he talks of joyous local church fetes, where ducks were won and cake sizes were to be guessed to the gram! He talks about his mother spending an entire day, with the Burmese neighbour next door, preparing Khao Suey (a Burmese noodle soup) from scratch. I’m amazed at the level of detail with which he remembers the big and the small things. And even more amazed at how food weaves these memories together for him.

“It’s basically butter with a bit of egg”

While Joe Uncle’s Durgapur experience had overtones of borrowed continental food, we took a few steps back in time to talk about his family’s deep culinary heritage. Born to a Parsi mother and a Jewish father, Joe Uncle’s plate of food was the history book I wish I had. I nudged him to describe the food of his childhood, in his grandparents’ home when they would go visiting. With every dish he described, it was evident that he was telling a story of a people who had gone to lengths to make India home.

Parsis, for instance, came to the Indian shores (through Gujarat) in the 7th century, post the fall of the Persian Empire. Legend has it that the Indian ruler of that time, sent the Persians a glass of milk filled to the brim, to indicate that there was no place in his kingdom for more people. The Persians (who later on became “Parsis”) dissolved a spoonful of sugar in the same glass. They promised the ruler that just like the sugar had sweetened the milk without displacing it, they would assimilate into the land without changing its character. Akuri, a dish of scrambled eggs with Indian spices, is one such dish that originates in the Bharuch region of Gujarat but patented by the Parsi community. “My grandmother would whip us plates of steaming akuri. It’s basically butter with a bit of egg!”, shares Joe uncle with a laugh. That and a simple bowl of dal taken to dal-heaven, with the addition of deep-fried onions and garlic, form distinct flavour memories of the times he spent with his mother’s Parsi family.

On his Indian-Jewish side, he speaks of the rustic kitchen in Byculla, Mumbai, where he would spend time with his paternal grandmother or Aai. Joe Uncle’s grandparents belonged to the Bene Israeli community of India. Lore has it that fleeing Jews arrived on the shores on the Konkan coast (western coastline of India) over two thousand years ago. They moved to Mumbai, and neighbouring regions, in the early 18th century and assimilated into the region, adopting its language (Marathi) and various culinary traditions. “Aai would put kothimbir (coriander) on top of everything!” shares Joe uncle, referring to Maharashtra’s favourite garnish. He also remembers her malty, salty gur chapatis (flatbreads filled with jaggery) and how vendors would stop by to sell treats like guava cheese (a chewy, fudge-like sweet snack made with concentrated guava jelly). Gauva cheese, he goes on to explain, was a popular snack in the 70’s, especially amongst the East Indian community of Byculla. It traces its roots to Portuguese colonies (where it is known as goibada) cleverly invented to protect sailors from scurvy by relying on the Vitamin C rich guava. While in the ’70s it adorned snack cabinets and helped aunties impress unexpected guests, today it survives as a snack of nostalgia.

A crackle from our Zoom call reminds me I’m on borrowed time. I snap back to the present and can hear Joe Uncle’s household stirring to get ready for breakfast, on the other side of the globe. As we wrap up, Joe Uncle tells me excitedly how just that morning, he was mowing his lawn and the smell of fresh grass reminded him of milk! Curious about that connection, he paused to explore that sensory response, only to remember that back in Durgapur the milkman would deliver milk with a cow chewing on grass. He was taken back to his doorstep, where his mother would chat with the milk-man as he milked the cow in front of her, while 10-year-old Jawahar, looked on. A memory of home that was up until now tucked away and suddenly triggered by the mere aroma of freshly cut grass and a seemingly mundane chore.

I pause to take a breath as I try to wrap my head around this web of intricately weaved identities. We’ve traversed centuries in this one conversation - from Colonial India to Persians and Jews arriving on the shores of western India, to even briefly stopping by to say hello to the East Indian community of Mumbai! I realise that between the folds of these memories of food, lay the history of a nation coming into its own.

Dates in dusty textbooks may indicate the start and end of events, but don’t account for memories that linger on. And it’s perhaps these memories that give weight to the hyphenated existence for many across the country today. And if one looks at that hyphen through the prism of food, one might probably see it as a bridge over which recipes are passed from one kitchen to another, holding the story a nation aching to find its identity.