Memories of an Unfinished Meal

Table Talk chats with Jigyasa as she traces her Kashmiri Pandit identity through plates of food tinged with love, loss and longing.

You know a good story from a great one when it begins in the winding lanes of the Silk Route. The Silk Route or Silk Road was an ancient network of trade routes that connected China in the east to the Levant in the west. While silk from China was the initial lure for this 4000 odd-mile caravan track, there was more that flowed through these routes. Culinary traditions along this route connected the east with the west like never before, and it appears that recipes for dumplings, bread and rice pilaf were exchanged as easily as one would over a fence, with a friendly neighbour.

The valley of Kashmir, nestled in the Himalayas, found itself uniquely positioned on this fabled, ancient route of trade. While handicrafts and textile industries made their mark on the valley, Saints, Sufis and Rulers chiselled away at the Kashmiri plate. Whether it’s the hum of saffron, the comfort of warm bread or the technique of tenderizing meat to perfection, Kashmiri food holds an expansive legacy.

On this morning, Jigyasa dials in from Dharamshala, a hillside city in India’s northern state of Himachal Pradesh. Jigyasa begins with an innocent and honest confession, “Growing up, I never thought much about food, even though food was central to my family. I gave them a tough time when it came to my food habits..funny because they were always talking about food, always thinking about the next meal!”

Jigyasa belongs to the Kashmiri Pandit community of Kashmir. Kashmiri Pandits are Hindu Brahmins who are believed to be the first settlers of the land. “But Kashmiri pandits are meat-eating Brahmins”, she points out to differentiate this community from the rest of India’s predominantly strictly vegetarian Brahmin community. Kashmiri Pandits traditionally prepare fish and mutton dishes on their holiest of days like Herath or Maha Shivaratri. They cook their meat without onion and garlic, distinguishing their cuisine from the Kashmiri Muslims, the other predominant community in Kashmir. “I remember the food at home being extremely flavourful and by that I mean you can taste the flavour of the meat or vegetable. No garlic and onions or even tomatoes, just meat and vegetables cooked in light spices. And I remember being told how that was typical to Kashmiri Pandit food – that our food was unique”, shares Jigyasa.

You know a good story from a great one when it begins in the winding lanes of the Silk Route. The Silk Route or Silk Road was an ancient network of trade routes that connected China in the east to the Levant in the west. While silk from China was the initial lure for this 4000 odd-mile caravan track, there was more that flowed through these routes. Culinary traditions along this route connected the east with the west like never before, and it appears that recipes for dumplings, bread and rice pilaf were exchanged as easily as one would over a fence, with a friendly neighbour.

The valley of Kashmir, nestled in the Himalayas, found itself uniquely positioned on this fabled, ancient route of trade. While handicrafts and textile industries made their mark on the valley, Saints, Sufis and Rulers chiselled away at the Kashmiri plate. Whether it’s the hum of saffron, the comfort of warm bread or the technique of tenderizing meat to perfection, Kashmiri food holds an expansive legacy.

On this morning, Jigyasa dials in from Dharamshala, a hillside city in India’s northern state of Himachal Pradesh. Jigyasa begins with an innocent and honest confession, “Growing up, I never thought much about food, even though food was central to my family. I gave them a tough time when it came to my food habits..funny because they were always talking about food, always thinking about the next meal!”

Jigyasa belongs to the Kashmiri Pandit community of Kashmir. Kashmiri Pandits are Hindu Brahmins who are believed to be the first settlers of the land. “But Kashmiri pandits are meat-eating Brahmins”, she points out to differentiate this community from the rest of India’s predominantly strictly vegetarian Brahmin community. Kashmiri Pandits traditionally prepare fish and mutton dishes on their holiest of days like Herath or Maha Shivaratri. They cook their meat without onion and garlic, distinguishing their cuisine from the Kashmiri Muslims, the other predominant community in Kashmir. “I remember the food at home being extremely flavourful and by that I mean you can taste the flavour of the meat or vegetable. No garlic and onions or even tomatoes, just meat and vegetables cooked in light spices. And I remember being told how that was typical to Kashmiri Pandit food – that our food was unique”, shares Jigyasa.

“You come of age when you can make the perfect cup of sheer chai!’’

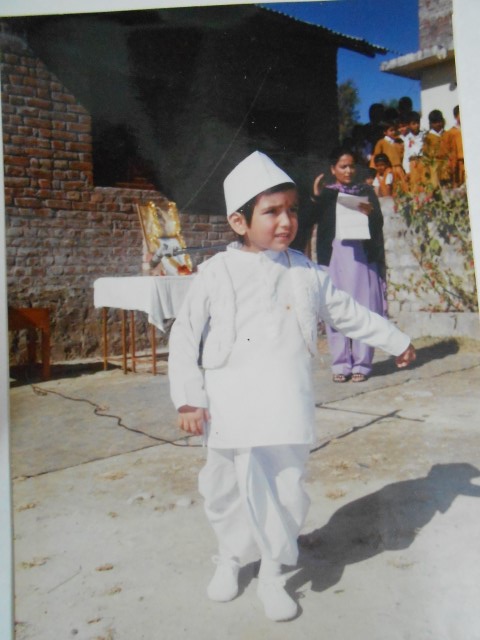

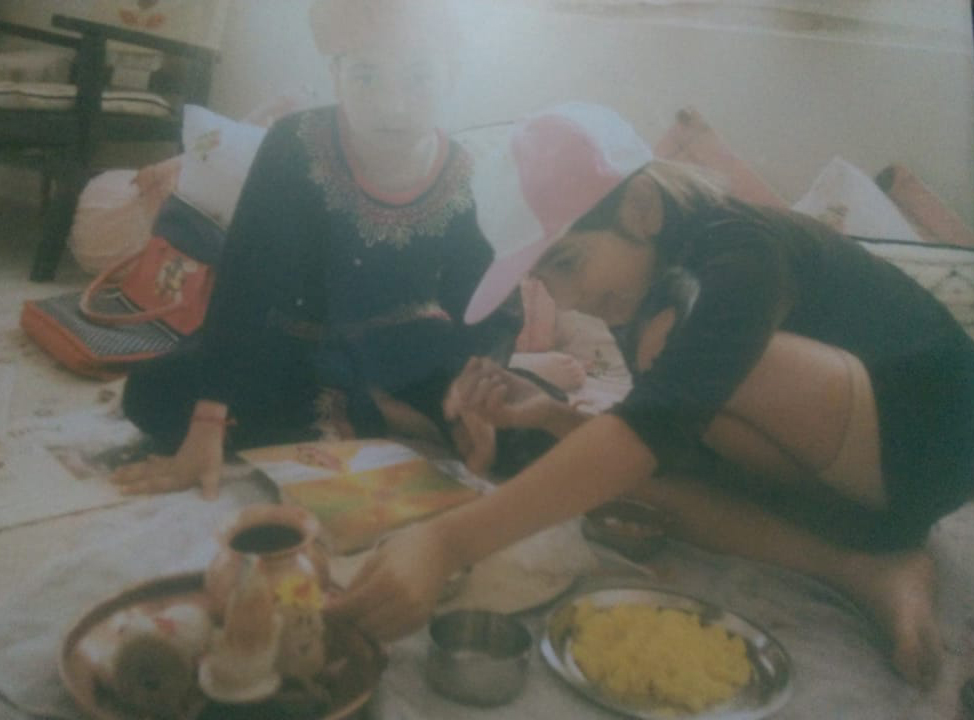

Jigyasa grew up in a home where honouring the Kashmiri Pandit identity, through language and food, was an essential way of life. All of this without actually living in or even visiting Kashmir, until much later. “I visited Kashmir for the first time only when I turned 22. My family left Kashmir in the exodus of 1990 after my mother’s home was burned down and generations worth of our family existence just vanished.” The Kashmiri Pandit exodus of 1990 is a marker in the history of the valley that irreparably changed the course for Kashmiri Pandits. Driven out of the valley and their homes as a result of Islamic militancy and political instability, Kashmiri Pandits have had to hold on to their notion of home tighter than they had ever anticipated. It is estimated that in the early part of 1990, over 75000 Kashmiri Pandits were driven out, followed by another 70000 in the following years. While Kashmiri Pandits migrated to places like Delhi, Agra, Lucknow, Pune and even to the southern Indian city of Chennai, Jigyasa’s family found itself in the quaint hilly town of Dharamshala. “I remember going to friends’ homes and noticing how people didn’t eat like how we ate at home. Like even the presence of dal everywhere puzzled me, because back home, dal was not a thing we ate regularly”, Jigyasa reminisces.

The Kashmiri Pandit plate is truly distinctive. While most Indian regional plates have some version of a dal, the Kashmiri plate makes do with mustard-oil-infused gravies. Meat (specifically lamb) and rice is central to every Kashmiri meal. “Pandits are big meat eaters. While I chose to turn vegan a few years ago, most home-meals involve a mound of rice and then a mound of meat on top of it!” shares Jigyasa. Meat is relished, whether it’s the qalia or yakhni (meat cooked in lightly spiced yoghurt gravy) or the rogan josh (meat gravy cooked with rich but mildly spiced Kashmir red chilli). Gravies are laced generously with hing (asafoetida) which defiantly steps in for the lack of garlic and onions. Spices like saunf (fennel), saunth (dried ginger) and methi (fenugreek) give the dishes its characteristic warmth and depth of flavour.

And while those are simple dishes that feature on the every-day menu, it’s the elaborate and carefully curated Kashmiri Wazwan that’s put this cuisine on the map. Common but varied to both the Hindu and Muslim communities, this 36-dish-feast features dishes like chaman qalia (a creamy cottage cheese dish flavoured with fennel and cardamom), goshtuba (meatballs cooked in yoghurt) or the elaborate kabargah, to name a few. Kabargah, which literally translates to burial ground, is a meat dish that’s cooked overnight in milk till it forms a char on the outside but retains its tenderness on the inside. Jigyasa also goes on to share, “It’s no wonder that women often ask each other “tsyun kya chi ronmut”, which roughly translates to, “what kind of meat have you made today” as a polite conversation starter.”

As far as the vegetarian dishes go, you soon realise they only come in as a strong second. Nadru yakhni (lotus stems cooked in spiced yoghurt), rajma gogji (red kidney beans cooked with turnips), dum aluv (baby potatoes in spices) and the all essential monji-haaq (kohlrabi greens) emerge as clear winners on the Kashmiri Pandit table. Haaq, quintessentially Kashmiri, is a green leafy vegetable (kohlrabi greens) indigenous to the Kashmir valley and an essential component of Kashmir’s culinary legacy. The greens are cooked in mustard oil and often spiced with the indigenous Kashmiri chilli.

The Kashmiri Pandit plate is truly distinctive. While most Indian regional plates have some version of a dal, the Kashmiri plate makes do with mustard-oil-infused gravies. Meat (specifically lamb) and rice is central to every Kashmiri meal. “Pandits are big meat eaters. While I chose to turn vegan a few years ago, most home-meals involve a mound of rice and then a mound of meat on top of it!” shares Jigyasa. Meat is relished, whether it’s the qalia or yakhni (meat cooked in lightly spiced yoghurt gravy) or the rogan josh (meat gravy cooked with rich but mildly spiced Kashmir red chilli). Gravies are laced generously with hing (asafoetida) which defiantly steps in for the lack of garlic and onions. Spices like saunf (fennel), saunth (dried ginger) and methi (fenugreek) give the dishes its characteristic warmth and depth of flavour.

And while those are simple dishes that feature on the every-day menu, it’s the elaborate and carefully curated Kashmiri Wazwan that’s put this cuisine on the map. Common but varied to both the Hindu and Muslim communities, this 36-dish-feast features dishes like chaman qalia (a creamy cottage cheese dish flavoured with fennel and cardamom), goshtuba (meatballs cooked in yoghurt) or the elaborate kabargah, to name a few. Kabargah, which literally translates to burial ground, is a meat dish that’s cooked overnight in milk till it forms a char on the outside but retains its tenderness on the inside. Jigyasa also goes on to share, “It’s no wonder that women often ask each other “tsyun kya chi ronmut”, which roughly translates to, “what kind of meat have you made today” as a polite conversation starter.”

As far as the vegetarian dishes go, you soon realise they only come in as a strong second. Nadru yakhni (lotus stems cooked in spiced yoghurt), rajma gogji (red kidney beans cooked with turnips), dum aluv (baby potatoes in spices) and the all essential monji-haaq (kohlrabi greens) emerge as clear winners on the Kashmiri Pandit table. Haaq, quintessentially Kashmiri, is a green leafy vegetable (kohlrabi greens) indigenous to the Kashmir valley and an essential component of Kashmir’s culinary legacy. The greens are cooked in mustard oil and often spiced with the indigenous Kashmiri chilli.

“For people who have lost their home, their connection with their land,

keeping traditions alive through food becomes a key priority.”

But the story of Kashmiri food is incomplete without the role of bread and tea. It is here that you clearly see vignettes of the bustling Silk Route - where it is believed that recipes to bake bread and brew tea were brought to the valley by traveling merchants. It is here that you see the distinct influence of Persia (through the baking process and the arrival of the tandoor) and Central Asia (through the use of the samovar to brew tea). While Kashmiris are staunch rice eaters, they are extremely partial to their bread. Kulchas, lavasa, bakarkhani, katlam are bread varieties that tell a story that stretches beyond geographical borders. The bread is often dipped in tea or sheer chai, a kind of tea unlike anything one finds in the rest of the country. Made with salt and not sugar, pink and not the usual brown, it is a cup of tea that only belongs to the valley of Kashmir. “You come off age when you can make the perfect cup of sheer chai! It’s a real skill to get the right shade of pink!”, shares Jigyasa who is not shy to hide her preference for the pink, salty version of the subcontinent’s favourite beverage.

Today, almost three decades after the exodus, Kashmiri Pandits excavate memories of a lost land through food, through unfinished meals. “For people who have lost their home, their connection with their land, keeping traditions alive through food becomes a key priority”, shares Jigyasa as she reflects on the changing Kashmiri plate. Over the years she has noticed how Kashmiri Pandit food is harder to find and even harder to share with the uninitiated. Restricted to family homes or mediocre versions in restaurants across northern India, the cuisine is destined to fight the paradoxical forces of relevance and remembrance.

While history lures us into a valley that was at the crossroads of cultural and culinary exchange, today the land finds itself strictly bound within the confines of volatile borders and conflicting ideologies. The culinary legacy of the Kashmiri Pandit community lives in the collective memory of the wider community, aching for revival. And as we continue to navigate thorny questions of home, identity and belonging, one probably just needs to circle back to the ever pertinent question, over the metaphorical fence, “tsyun kya chi ronmut”?

Today, almost three decades after the exodus, Kashmiri Pandits excavate memories of a lost land through food, through unfinished meals. “For people who have lost their home, their connection with their land, keeping traditions alive through food becomes a key priority”, shares Jigyasa as she reflects on the changing Kashmiri plate. Over the years she has noticed how Kashmiri Pandit food is harder to find and even harder to share with the uninitiated. Restricted to family homes or mediocre versions in restaurants across northern India, the cuisine is destined to fight the paradoxical forces of relevance and remembrance.

While history lures us into a valley that was at the crossroads of cultural and culinary exchange, today the land finds itself strictly bound within the confines of volatile borders and conflicting ideologies. The culinary legacy of the Kashmiri Pandit community lives in the collective memory of the wider community, aching for revival. And as we continue to navigate thorny questions of home, identity and belonging, one probably just needs to circle back to the ever pertinent question, over the metaphorical fence, “tsyun kya chi ronmut”?